Welcome to history podcast number 93. This episode is a request via email from Ruth Campbell. Ruth wants to know more about Pope Joan.

Joan, Pope, legendary female pontiff who supposedly reigned under the title of John the VIII, for slightly more than 25 months, from 855 to 858, between the pontificates of Leo IV (847 – 855) and Benedict III (855 – 858). It has subsequently been proved that apocryphal.

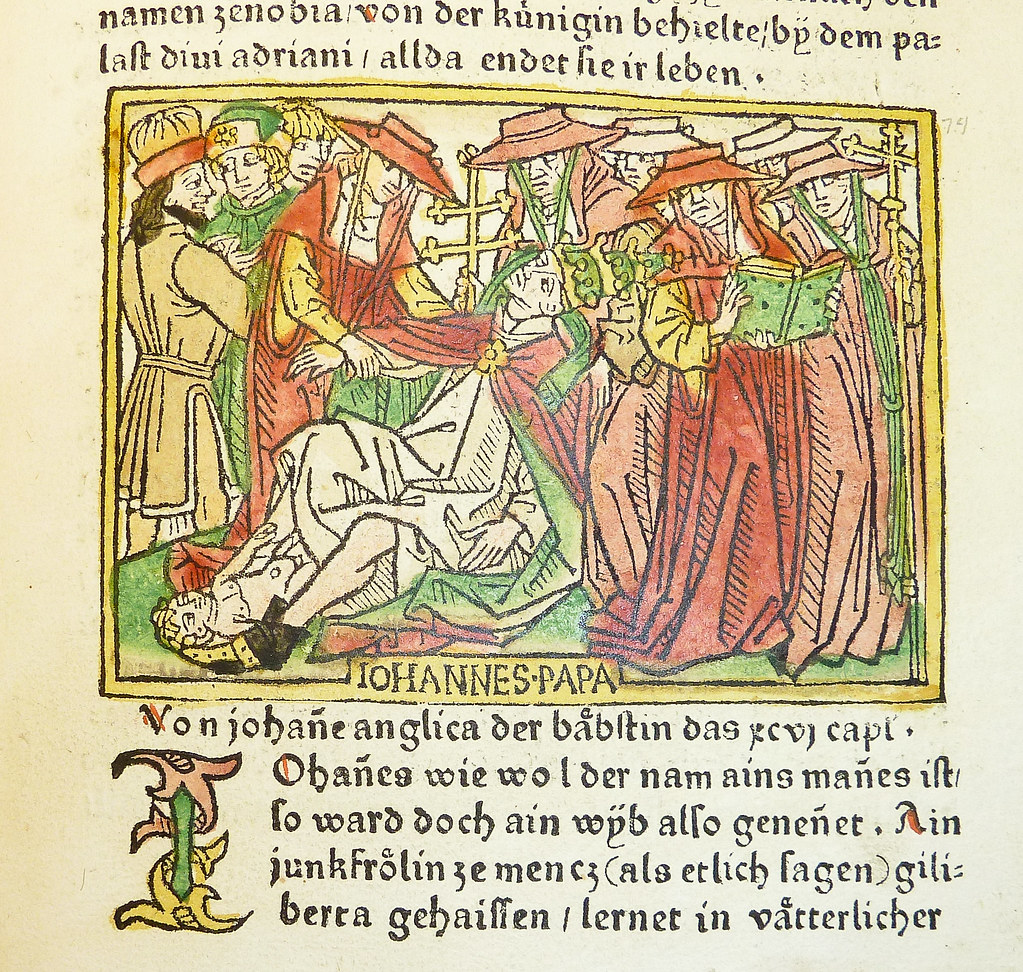

One of the earliest extant sources for the Joan legend is the De septem domis Spiritu Sancti (“The Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit”) by the 13th century French Dominican Stephen of Bourbon, who dated Joan’s election c. 1100. In this account the nameless pontiff was a clever scribe who became a papal notary and later was elected pope; pregnant at the time of her election, she gave birth during the procession to the Lateran, whereupon she was dragged out of Rome and stoned to death.

The story was widely spread during the later 13th century mostly by friars and primarily and primarily by means of interpolations made in many manuscripts of the Chonicon pontificum et impertorum (“The Chronicle of the Popes and Emperors”) by the 13th century Polish Dominican Martin of Troppau. Support for the version that she died during childbirth and was buried on the spot was derived from the fact that in later years papal procession used to avoid a particular street, allegedly where the disgraceful event had occurred. The name Joan was not finally adopted until the 14th century; other names commonly given were Agnes or Gilberta.

According to later legend, particularly by Martin (who dated her election 855 and who specifically named her Johannes Angelicus), Joan was an Englishwoman; but her birthplace was given as Mainz (now in Germany), which some writers reconciled by explaining that her parents migrated to that city. She supposedly fell in love with and English Benedictine monk and, dressing as a man, accompanied him to Athens. Having acquired great learning, she moved to Rome, where she became a cardinal and pope. From the 13th century the story appears in literature, including the works of the Benedictine chronicler Ranulf Higden and the Italian Humanist Giovanni Boccaccio and Petarch.

In the 15th century Joan’s existence was regarded as fact, even by the council of Constance in 1415. During the 16th and 17th centuries the story was used for protestant polemics. Such scholars as Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, afterward Pope Pius II, and Cardinal Ceasar Baronius regarded the story as unfounded, but it was the Calvinist David Blondel who made the first determined attempt to destroy the myth in his Elaircissement familier de la question: Si une femme a ete assie au siege papal de Rome (1647; “Familiar Enlightenment of the Question: Whether a Woman Had Been Seated on the Papal Throne in Rome”). According to one theory, the fable grew from widespread gossip concerning the influence wielded by the 10th century Roman woman senator Marozia and her mother Theodoria of the powerful house of Theophylact.

The second edition of J.J.I. von Dollinger’s Die Papstfabeln des Mittelalters (“Fables about the Popes of the Middle Ages”) was published in 1890. Another study of the Pope Joan question is contained E. Vacandard’s Etudes de critique et d’histoire religieuse, 4 vol. (1909-23; “Studies of Criticism and of Religious History”).